What drew you to translate this book?

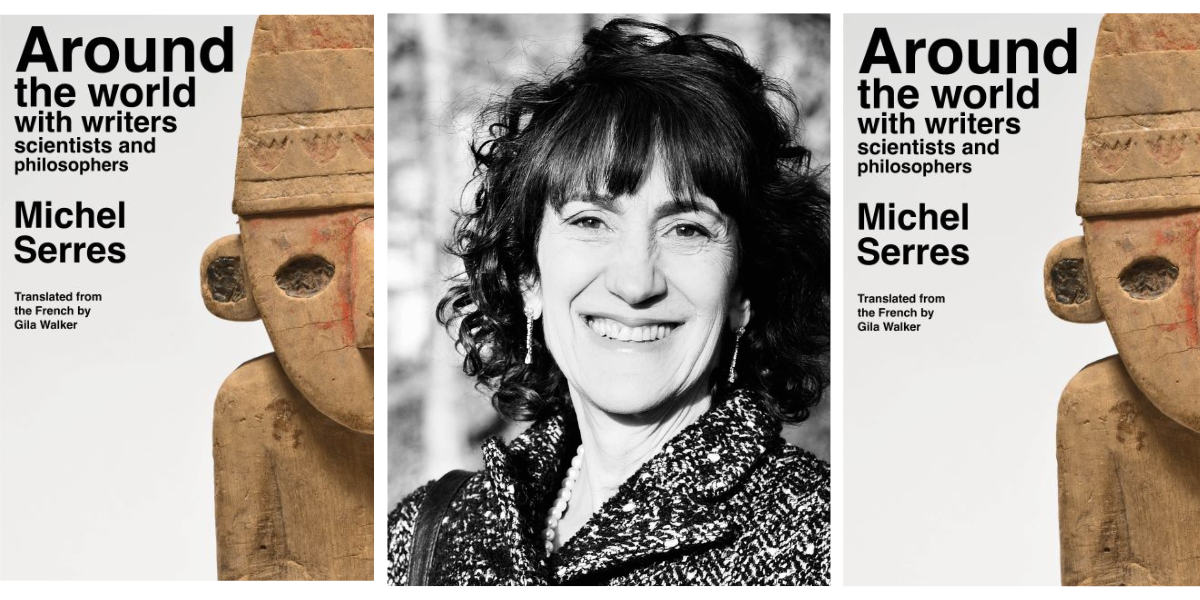

It was Gazebo Books publisher, Xavier Hennekinne, who, after reading a number of my translations for Seagull Books, reached out to me with the proposition to translate a book by one of his most beloved writers and thinkers Michel Serres, and I jumped at the chance. I must confess that I’d never read anything by Serres before, although I was familiar with his reputation, of course. I’ve an extensive familiarity with French philosophers and have had the good fortune to translate texts by Derrida, Todorov, Didi-Huberman, and François Julien, among others, but somehow, I’d never turned my attention to Serres, possibly because he was something of an outlier in many respects. This was, incidentally, the reason he never really found a home within the French university system and taught instead in the United States, at Stanford University, California.

So, when Xavier approached me with this proposal, I was immediately game and very excited by the idea of delving into Serres’ universe and delve I did for over a year.

What would you say drew you to translation work in general?

I’ve always been an avid traveler. In my youth, when I’d set out on a journey, I’d often enjoy leaving the destination to chance. I’d hitch a ride with no particular end in mind and go wherever the ride would lead me. Traveling has been one of the great joys of my career as a translator. Delving into the writings of others as I do when I’m translating gives me the exhilarating feeling of exploring new depths and horizons, but also of going to places where I may not have ventured of my own devices. Which brings us right back to this book by Serres.

Traveling is very precisely what Around the World with Writers, Scientists and Philosophers is all about.

Can you elaborate?

Serres takes the reader on a journey across time and space, leaping over divides between disciplines, knocking down boundaries between hard and soft sciences, history, literature, philosophy, art, religion, and technology. And he does so seamlessly and with astonishing freedom – sometimes within the space of a single paragraph, if not a sentence – and with contagious passion, exuberance, and enthusiasm.

There may not be a single entry point into Serres’ corpus, no one book that everyone agrees is the best place to start but, to my mind, Around the World with Writers, Scientists and Philosophers is as good a place as any to get a sense of the extraordinary vitality of Serres’ encyclopedic mind.

What were the specific challenges involved in the translation of this book?

One of the challenges in translating Serres, and there are many, is rendering his mix of tones and a prose style that is literary verging on poetry. His free-wheeling artful prose is one of the reasons that he was and is still seen as an outlier among French philosophers.

Another challenge to the translator is the practically innumerable hidden references, allusions and citations. That Serres most often deliberately refrains from putting citations between quotation marks or adding footnotes presents a unique challenge to the translator. Then there are the word-plays and the threads he draws from words based on the meaning of their roots in Latin and Greek, and their Old French and modern-day usage.

Could you tell us something about your experience translating literature?

I grew up in a modern orthodox Jewish family, immigrants from Eastern Europe who spoke multiple languages. Interpretation was the fabric of the world into which I was born. I drank it with my mother’s milk, was raised and schooled in it. It is second nature to me. Studying Scriptures was less about truth than about exploring commentaries of the past. And we were encouraged to add our own interpretations to the thousands of years of this hermeneutic tradition.

I like to compare the process of translation to the story in the Bible of Jacob at Peniel wrestling all night long with an ish – a man, or a divine agent or angel as some commentators would have it, or Esau’s guardian angel as the greatest of all medieval commentators Rashi from Troyes suggests. The fight, which ends at dawn, leaves Jacob injured, with a permanent limp, but also with a new name.

This image of wrestling with the other (or does va-ye’avek, usually translated as wrestling, mean clasping or twining or kicking up dust) is, to my mind, a perfect metaphor for the act of translating, and its transformative impact, intellectually, to be sure, but also emotionally and even physically. I like to think that, as a translator, I come out of this struggle, this grappling, this clasping, with a new identity. The translation is authored neither by a pre-existing me, by me as I was when I first came to it, nor by the writer of the original text in French, but by a new being created through this struggle or embrace, which leaves me, the translator, changed, if not injured.

And lastly…

Favourite bookshop anywhere in the world?

Librairie Mollat without a question. It is the largest independently owned bookstore in France and an institution in Bordeaux. The store is huge and well-stocked, and the staff is amazingly well informed. I don’t know of another bookstore of this size that can boast a staff that actually knows the books in its many and varied departments.

What’s the last translated book you read that you loved?

I recently finished a three-volume book The Tree of Life: A Trilogy of Life in the Lodz Ghetto by Chava Rosenfarb. Originally written in Yiddish, Rosenfarb translated it herself with her daughter Goldie Morgentaler. Considering the subject matter, it’s an astoundingly life-affirming book, as its title aptly indicates.