What compelled you to pursue the art of translation?

I became interested in Japanese literature as a teenager, drawn to the works of authors like Yasunari Kawabata, Yukio Mishima, and Kōbō Abe. At the time, the selection of Japanese books available in English wasn’t as broad as it is today, and I soon realised that many works by these and other authors remained untranslated. As I read more, I also became aware of how much the translators shaped the books I loved how their choices played a key role in bringing these works to life in English. My initial desire to read the missing pieces gradually grew into a fascination with translation itself, along with a desire to bring more of Japan’s unique literary voices to English-speaking readers.

Literary translation is a mysterious job to most. What is an ordinary day of work like for you?

Translation is a mix of deep concentration and problem-solving. I typically spend a few hours at a time working through a text, carefully choosing the right words and phrasing to convey the author’s tone and intent. Along the way, I’ll pause to research references or allusions that might come up, reread sections to refine the flow, and sometimes step away from the text to let tricky passages sit before coming back with fresh eyes. It’s a process of constant adjustment and refinement.

What is the most challenging part of translating from the Japanese?

The biggest challenges are often cultural. There are many seemingly straightforward words and concepts in Japanese that don’t quite have direct equivalents in English because they reflect a different social attitude or philosophical worldview. One famous example is gaman, which is sometimes translated as ‘patience’ or ‘endurance’, but that, in Japanese culture, means much more than simply waiting calmly. Gaman carries a strong sense of quiet perseverance and self-sacrifice – it’s about enduring difficulties without complaint, maintaining your dignity, and not imposing on others. This kind of cultural nuance is the hardest part of translation – you often have to go beyond the words themselves to make sure the deeper meaning and emotional weight carry over into English in a way that feels natural to the reader.

What is the most enjoyable part of translating from the Japanese?

I love immersing myself in an author’s unique style and figuring out how to carry that same tone and atmosphere into English. The two languages and cultures are very different, so you have to constantly experiment with different word choices, adjusting sentence rhythms, seamlessly providing necessary context, and finding just the right balance between accuracy and natural flow. There’s an almost puzzle-like satisfaction in getting a story to feel ‘right’ in English while still staying true to the original.

You hold a PhD in Japanese literature from Monash University. How did this help refine your interests and goals as a translator?

My PhD focused on literary stylistics and creative approaches to translating grammatical and cultural non-equivalences between Japanese and English. The knowledge and experience I gained from it have been invaluable in my translation projects, equipping me with the skills to maintain fidelity to the source text while prioritising readability for English-speaking readers.

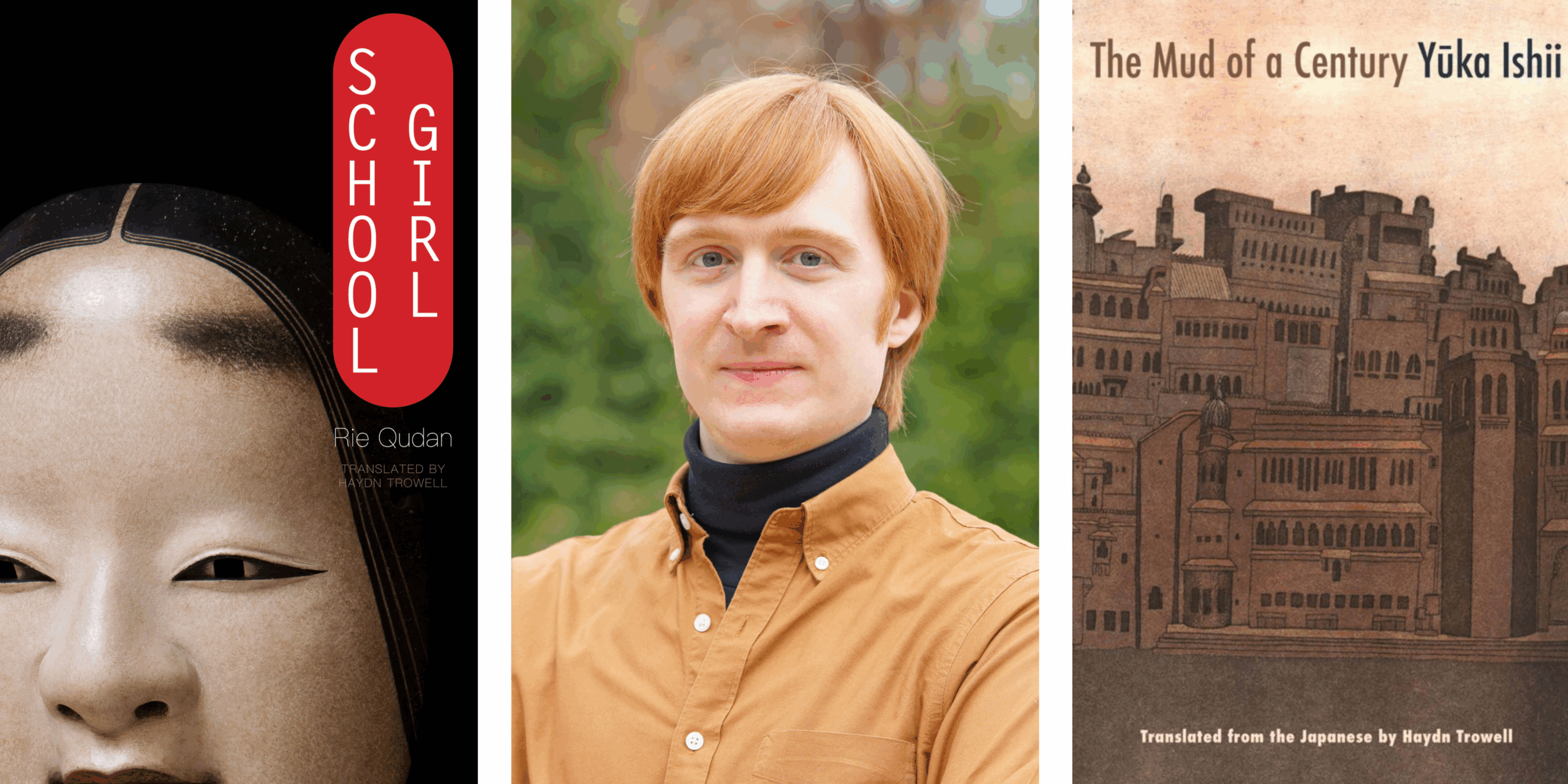

What do you hope that Japanese literature – such as Schoolgirl and The Mud of the Century – brings to Australian and New Zealander readers?

One of the paradoxes of translated literature is that by stepping outside our own cultural context, we often find a clearer path to self-reflection. Sometimes, it’s easier to look critically on aspects of ourselves through the lens of another culture, as reading about characters navigating unfamiliar worlds can open our eyes to things we might usually take for granted. With books like Schoolgirl, I hope Australian and New Zealander readers not only get to step into a Japanese context but can also find points of connection with the characters and their experiences.

Is there a book you want to translate next, and why?

I’d love to translate more works by Yasunari Kawabata, who has a few titles that still haven’t been translated into English. Whether it’s the shifting seasons, the fleeting beauty of a landscape, or the quiet rituals of daily life, he has an extraordinary ability to convey complex feelings through sparse, elegant imagery.

Favourite bookshop anywhere in the world?

Choosing a favourite bookshop is a bit like picking a favourite book. As long as it has an extensive world literature section, I’ll be happy.

What book are you currently reading?

Mina’s Matchbox by Yōko Ogawa.

What’s the last book you read that you loved?

The Blue Fox by Sjón.